Table of Contents

Figure 1: Abstract illustration of student privacy and AI integration

7-minute read

An Unexpected Difference

I've been a Google Classroom user for over five years and appreciate the way it's upgraded my teaching practice. I no longer have to carry stacks of papers home for grading. I can provide detailed feedback that students actually read. My course materials are accessible from anywhere. My students can build their own learning archives. Honestly, it’s been awesome. But Google's newest AI tools for education have me asking questions I didn't expect.

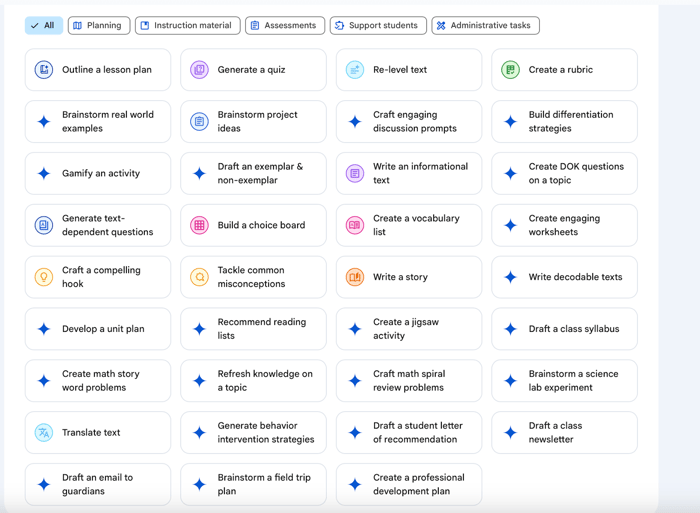

As I was exploring their new education suite this summer with AI tools for everything from lesson planning to quiz generation to creating rubrics and dozens of other teaching tasks, I noticed something different about the “draft a student letter of recommendation” feature. Unlike the other tools, this one specifically asked for student information. With recommendation season approaching as these new Google tools launch, this difference seemed worth a closer look. While there are legitimate questions about whether AI should assist with recommendation letters at all (be still my English teacher heart), understanding how these tools handle student information and shape the writing process becomes important as they become available to educators.

Figure 2: Google AI Tools for Education interface showing a selection of available AI tools

The Privacy Concern

When I clicked on Google's recommendation tool, I found a template that asks teachers to provide the student's full name, positive qualities to highlight, the purpose of the letter, and concrete examples for each trait. Once entered, the tool uses this information to generate a draft. Templates. Automation. Simplicity. What could be better? (More English teacher irony).

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) protects student educational records and personal information. Teachers aren't allowed to share student names, grades, or performance details without the appropriate consent. To be clear, Google's Workspace for Education provides significant privacy protection. The AI tools don't use data to train models and come with enterprise-grade safeguards that keep everything within the school domain, so the concern isn’t about security in this instance.

The real issue lies in the habits we're building. Google includes a clear warning in their training materials: "Please don't enter private or confidential information in your Gemini conversations or any data you wouldn't want Google to use to improve its products, services, and machine learning technologies." Yet the same suite of AI offerings introduces tools that specifically request student names and personal information. I know, it’s confusing. And it creates a privacy paradox that sends mixed messages about the data standards we expect teachers to uphold when using large language models (LLMs).

Figure 3: Google's letter of recommendation tool interface showing student information requests

I've worked with hundreds of teachers in professional development sessions on responsible AI use. When I mention that student names and identifiers shouldn't be entered into LLMs like ChatGPT, some teachers have responded with some version of, "I hadn't even thought about that." That's not negligence; it's a sign of how fast the landscape is shifting. Teachers are balancing lesson planning, instruction, grading, and administrative responsibilities every day. They are overloaded. When a tool promises to save time, it's easy to focus on the output rather than the input. Over time, that shortcut becomes a habit, and the habit becomes a default.

The concern extends beyond the immediate context. While Google's education-based system provides significant protections, teachers often work from home or use personal devices to complete tasks (like letters of recommendation!). When entering student information into AI tools becomes normalized practice, that behavior can transfer to less secure environments where teachers might unconsciously apply the same data practices with ChatGPT or other consumer LLMs. And that’s a safety issue.

The solution could be as simple as adding privacy disclaimers within individual tools rather than relying solely on training materials teachers may not have encountered. But common sense can guide us here too. Privacy protocols become habits of mind when applied thoughtfully.

Practical privacy approaches include:

Default to privacy-first practices: use first names only or student initials in AI prompts

Apply the "email test.” – if you wouldn't put student details in an unsecured email, don't put them in an AI prompt

Question any tool that requests full student identifiers

Integrate AI ethics into existing tech training through 10-minute faculty meeting segments on AI privacy reminders and peer mentoring where thoughtful AI users share privacy-conscious practices

The Design Question

Beyond the privacy concern, there's also a fundamental design question about what these tools encourage. Khan Academy's Khanmigo letter of recommendation tool asks similar questions but takes a different approach. It asks only for the student's first name and presents the questions in a clean form format rather than within a letter template. My favorite part, if I’m on board with any type of AI assisting in letters of recommendation, is that it includes a specific question about growth opportunities. This encourages teachers to reflect on areas where students might develop further, potentially making for a much more authentic letter.

Figure 4: Khan Academy's Khanmigo letter of recommendation interface showing reflective prompts

Google's approach streamlines the process for busy educators, but it feels more like filling out a form than crafting authentic reflection. There's certainly a time and place for automation in education. Tools that generate quizzes and create lesson plan templates can save time when teachers carefully evaluate the outputs and customize them for their specific contexts. But letters of recommendation present a different challenge. The automation that works well for quiz generation seems like the wrong fit for writing about students. This shouldn't be plug and play. Even if Google intended for teachers to generate drafts and then customize them, the template design encourages data entry over reflection. When tools encourage deeper reflection in their inputs, they support more authentic thinking in their outputs. This isn’t rocket science; it’s simply good practice. Better prompting approaches will generate more authentic material to begin with.

Thoughtful tool evaluation considers:

Does this tool position the educator as the primary thinker and author?

Do the prompts encourage reflection or just data entry?

Is automation appropriate for this particular educational task?

What habits does this tool's design encourage over time?

Our Responsibility in the Digital Age

As educators, we're trained in many ways to protect students. That includes everything from mental health protocols to emergency drills. Each morning, our staff balances welcoming students with maintaining campus security protocols. It's demanding work, especially in the rising Florida heat, but it reflects how seriously we take student safety.

That same care should extend to digital tools. Students are building digital footprints that will follow them long after they leave our classrooms. Most of them don't yet understand the long-term implications of data exposure. That responsibility falls to us. We have systems to protect students from physical harm; we need equally thoughtful systems to protect their digital identities, especially when they don't yet know what's at stake.

Building Sustainable Practices

But because technology is changing so rapidly, the real AI integration happens beyond initial professional development when thoughtful practices become habitual. So how does privacy-conscious prompting and intentional tool selection become a natural part of teaching and learning?

This requires creative approaches to maintain momentum between formal training sessions:

Weaving AI considerations into regular department conversations

Designating someone to share updates about new features and best practices

Incorporating these discussions into existing professional conversations about effective teaching

Developing student-led AI coaching programs as collaborative models

Most importantly, we need to help educators recognize that even the smallest decisions, such as what information to include in a prompt or which tool design philosophy to support, can shape long-term habits. Students don't get to choose which tools are introduced into their learning. They don't get to control how their information is used. We do. And that means we need to lead with intention, not just innovation.

About the Author: Michele Lackovic is an International Baccalaureate Workshop Leader, Senior Examiner, and author who works as a teacher and coordinator in Palm Beach County, Florida. She co-authored English A Literature for the IB Diploma (Pearson) and the upcoming IB Extended Essay Guide (HarperCollins, 2025) which includes AI guidance for research and citation. She has trained educators globally on AI integration in education and leads professional development on responsible AI implementation in classroom settings.

Works Cited

Google for Education. "Google Workspace for Education Training Materials." Google for Education, 2025.

Google Gemini. "Draft Letter of Recommendation." Google Workspace for Education, 2025.

Khan Academy. "Letter of Recommendation." Khanmigo, 2025.

OpenAI. "Student Privacy & AI Integration (Abstract Watercolor Illustration)." 2025. Generated by OpenAI, https://openai.com.

U.S. Department of Education. "Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)." ED.gov, www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/ferpa/index.html.

Find out more at www.myibsource.com